About That Sweetener Study

Mar 14, 2023

Over the past few weeks I decided to take a break from producing health related content both here and on my youtube channel. In part that’s because my health coaching business has been growing and I find that I need to spend my time serving the needs of my clients - many of whom have serious health issues - rather than producing content for the general public. The break gave me a chance to reflect on what it is we’re doing in the nutrition and health space.

During this hiatus, a lot of research has been published and some of that published research has made headlines. One paper in particular caught my eye. The paper exemplifies everything wrong with nutrition research at the current moment. The study - “The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk” - has made headlines on Fox, CNN, WebMD and elsewhere.

From the study’s title and the way it’s been written about, you’d be forgiven for concluding that the verdict is in. Erythritol - a non-nutritive sweetener that's become popular in recent years - causes heart disease. Case closed, thanks for playing, avoid this stuff like the plague.

But that’s not what the study says. And when you put together the various threads from the study, you might question why this paper was ever published at all.

So what does the study say? The paper is really two studies combined. The first was a study of about 3,000 people who were already at risk for cardiovascular disease. It divided people up based on blood levels of erythritol. Those with higher levels of erythritol in the blood were four times more likely to die of heart disease than those with lower levels of erythritol in the blood.

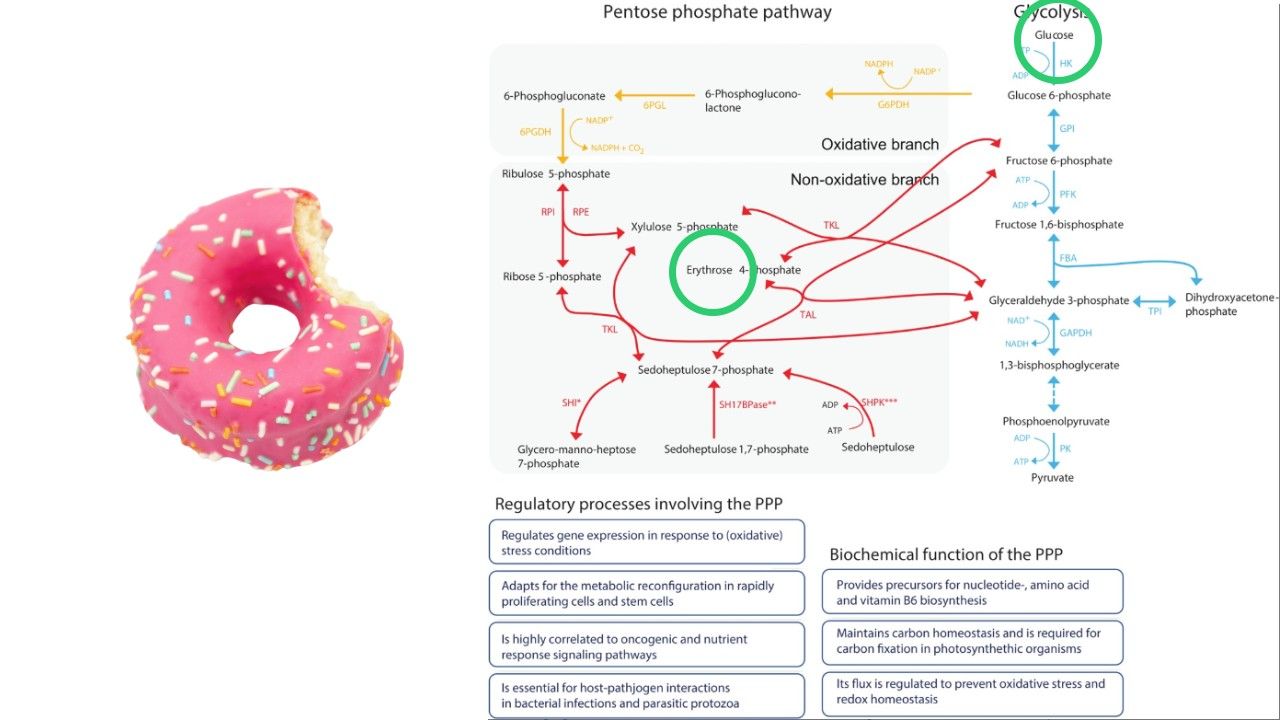

This data was collected long before erythritol became a popular sugar substitute. The erythritol in the subject’s blood was therefore exclusively the result of endogenous erythritol production. The body makes its own erythritol through what’s known as the pentose phosphate pathway. The pentose phosphate pathway is related to glucose disposal and oxidative stress and is thought to play a role in why we get diabetes, cancer and other metabolic diseases.

In other words, when you’re more metabolically dysfunctional - which is almost always related to consuming too much sugar and too many carbohydrates - your body produces more endogenous erythritol. Measuring erythritol in the blood had been recommended in one of the papers I’ve linked to above as an alternative to testing Hemoglobin A1C as a marker for metabolic dysfunction and diabetes. In other words, blood erythritol can be a substitute for testing blood sugar - it can tell you the same thing. And we certainly know that high blood sugar is strongly associated with heart attacks and other cardiovascular injuries.

The group that had low erythritol (and lower risk of disease) had 4 micromole per litre of erythritol in their blood; the group at higher risk had about 6 micromole per litre of erythritol in their blood. Those numbers will become relevant in a moment.

In the other arm of the study, they took eight individuals and gave them a fairly high dose of exogenous erythritol as a sugar substitute - about the same dose as might be found in a pint of diet ice cream or a six pack of erythritol sweetened soda. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study found that drinking erythritol increases the amount of erythritol in the blood. The amounts of erythritol in the blood of these subjects was orders of magnitude higher than that found in the metabolically unhealthy heart disease patients. The amounts went up to 7,000 micromole and stayed there for a few days. That's more than a thousand times higher than was found in the high risk group in the other arm of the study.

Aside from that one finding - that drinking it increases the blood concentration - the second arm of the study doesn’t tell us anything of significance. These subjects were not monitored for heart disease, they weren’t assessed for metabolic syndrome or for risk of cancer or diabetes or anything. So one could reasonably ask if it’s relevant that the blood concentration went so high. Based on the fact that these eight subjects assumably weren't instantly dying of heart attacks, their blood erythritol concentrations had no apparent bearing on health outcomes.

This paper is a bait and switch. One study clearly shows that endogenous erythritol in the blood is associated with bad outcomes (which was already known) and another study shows that exogenous erythritol raises levels of blood erythritol (which is common sense). There is no apparent link between the two.

When you think about it, the study may show the opposite of what it claims to. Endogenous erythritol production is related to sugar intake, and there is no doubt that sugar intake is causally associated with bad outcomes when it comes to heart health. So in the arm of the study that tracked outcomes, blood erythritol level was a surrogate marker for dietary sugar and carbohydrate intake.

If you’re worried about your heart health, one of the best things you can do is to stop or greatly reduce your intake of dietary sugar. If erythritol or other non-nutritive sweeteners can be a tool to help you do that, it’s a tool you should probably be using. There may or may not be issues with dietary erythritol and other non-nutritive sweeteners, and I hope to get into some of the details around that in the future. But based on the overwhelming evidence, issues with most non-nutritive sweeteners pale in comparison with the well understood harms of sugar and dietary carbohydrates. For many people, using artificial sweeteners can help reduce or even eliminate sugar from the diet. Given the state of our collective chronic health, that's not a tool we can afford to ignore.

So why would someone even publish this study? Imagine that you represent the interests of Coke, Pepsi, or one of the other brands listed in the graphic below. What are the biggest threats to your profits? How can you convince people that your product is healthy? Or, if not healthy, how do you convince them that the competitor's products are also unhealthy? And why, despite the fact that this study is one of the least interesting studies that I’ve read this year, has it received so much media coverage?

Regardless of the answers to these questions, this is a shoddy study that received an unwarranted amount of press coverage. The conclusion we can draw from that fact alone is that when it comes to health and nutrition at a societal level we are paying attention to the wrong things.

We know that increased sugar and carbohydrate consumption is driving increased rates of chronic disease including the major killers - heart disease, cancer and dementia. When determining what to eat (and what not to eat), we should probably focus a lot more on a simple principle - reduce sugar and carbs - and worry less about things that remain unclear.

🌱 Ready to Find Your Path to Gut Freedom?

Stop trying to solve your Crohn's, Colitis, or IBD alone with conflicting advice. A personalized plan is the fastest way to clarity and relief.

On a free call, you’ll get:

✅ Clarity on your triggers – Identify the dietary and lifestyle factors uniquely impacting you.

✅ A tailored starting point – Get actionable steps to reduce inflammation and calm your gut.

✅ Real answers – Ask anything about your symptoms and healing (no topic is off-limits).

💬 “Working with Sameer gave me a clear path when I felt completely lost. This is the guidance I needed.” – Previous Client

Your personalized plan is a conversation away.